Dance in the Country: A Glimpse Into Joy

In the golden heart of the 19th century, when the air of France was thick with the music of change and the scent of artistic revolution, one man painted the rhythm of happiness. Pierre-Auguste Renoir, one of the great masters of Impressionism, gifted the world a painting so alive, it seemed as though the brushstrokes had captured time itself mid-sway. That masterpiece is Dance in the Country (La Danse à la campagne), a celebration of joy, movement, and human connection.

But what is this painting really about? What story does it tell? What did Renoir want us to feel as we stepped into this moment suspended in time? And where can we see this radiant dance today?

Let’s step into the world of Renoir and discover the meaning behind Dance in the Country, its style, its setting, and its legacy.

The Brushstroke of a New Era

To understand Dance in the Country, we must first meet the artist who brought it to life. Pierre-Auguste Renoir was born in 1841 in Limoges, France. As a young boy, he showed early signs of creative genius. Apprenticed as a porcelain painter in his youth, Renoir developed a sharp eye for detail and a love for vibrant color, two qualities that would define his later masterpieces.

Renoir became a leading figure in the Impressionist movement, which emerged in the 1860s as a response to the rigid formalism of academic painting. Alongside Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and others, Renoir broke away from the dark interiors and idealized historical subjects that dominated French art. Instead, they painted the world around them, sunlight filtering through trees, laughter echoing in Parisian cafés, the glint of light on water, the spontaneity of real life.

And what could be more real, or more joyous, than a dance?

The Meaning of Dance in the Country

Painted in 1883, Dance in the Country (French: La Danse à la campagne) is more than a simple depiction of two people dancing. It’s a vibrant embodiment of warmth, intimacy, and shared delight.

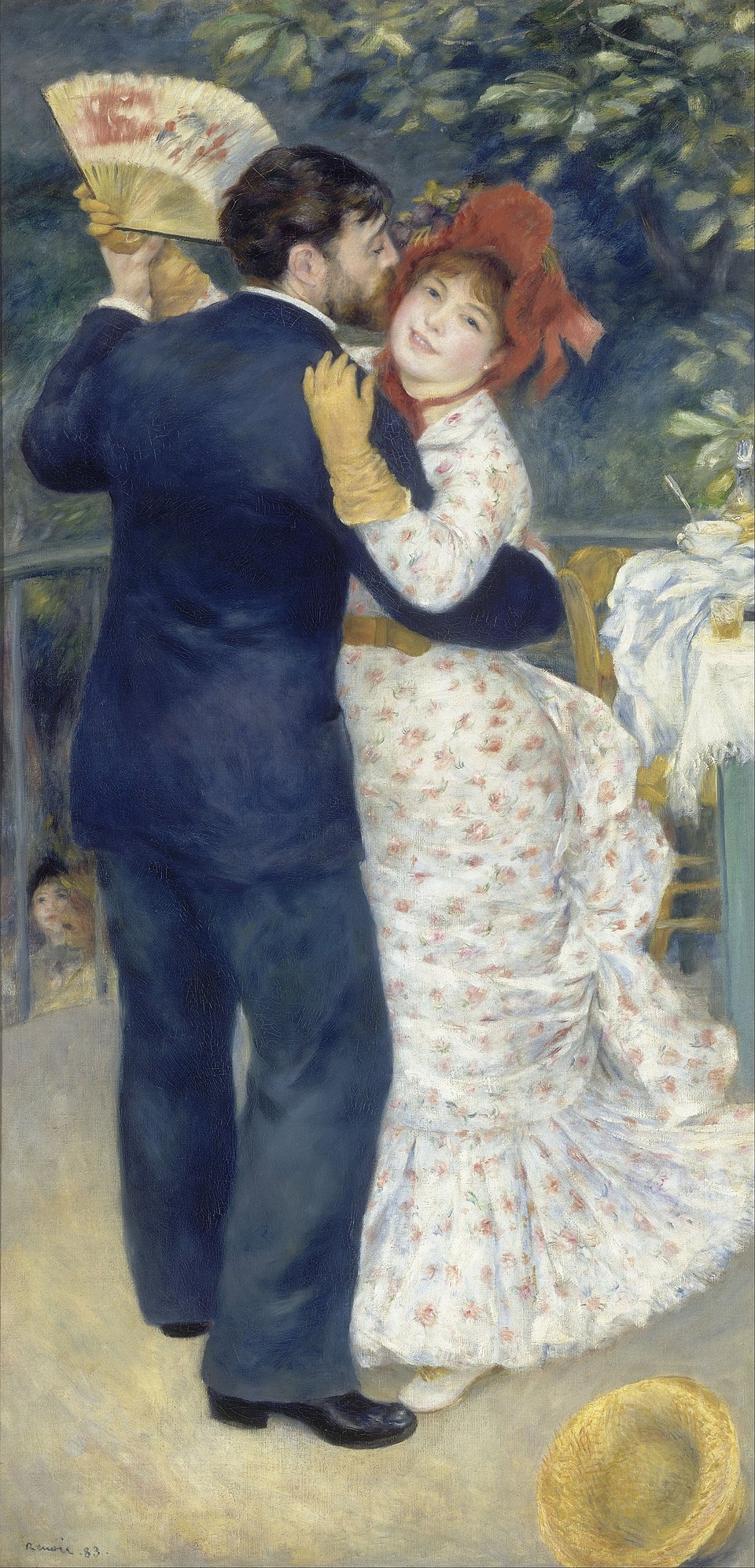

At first glance, we see a man and a woman mid-step, caught in a swirl of motion. The woman, radiant in a light dress with red accents, tilts her head toward her partner, smiling with unguarded affection. The man, clad in a dark suit and straw hat, gazes at her intently, their hands clasped. Behind them, a scattering of chairs and tables suggests a countryside café or perhaps a rural festival. The scene is bathed in soft sunlight filtering through the trees.

This is no grand ballroom, this is a dance of the people. A moment of simple pleasure, unencumbered by status or pretension. The countryside setting evokes a sense of peace and freedom, far from the bustling city and its social demands.

The Lovers and the Muse

The man in the painting is widely believed to be Paul Lhote, Renoir’s close friend. But the true star is the woman: Aline Charigot, Renoir’s lover at the time, and his future wife. Aline, with her soft features and joyful presence, appears in many of Renoir’s works. Here, she glows with life and affection, a living embodiment of Renoir’s ideal of feminine beauty.

Their dance is more than a literal one; it’s a metaphor for romance, for connection, for harmony. There is no stiffness or formality, just two people moving in time together, lost in each other and in the music of the moment.

What Type of Painting Is Dance in the Country?

Dance in the Country is often categorized as an Impressionist work, but by 1883, Renoir had begun to move away from the pure Impressionist style that defined his earlier career.

After a trip to Italy in 1881–82, where he studied the works of Renaissance masters like Raphael, Renoir started to shift his artistic approach. He became more interested in line and structure, moving away from the loose, spontaneous brushstrokes of early Impressionism toward a more classical and composed style.

This transitional phase is often called Renoir’s “Ingres period” (named after Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, a neoclassical painter admired for his draftsmanship). Renoir still captured light and movement, but with greater attention to form and volume.

In Dance in the Country, we see the blend of these influences. The colors are luminous and joyful, true to Impressionism. The setting is light-dappled and natural. But the figures themselves are more solid, sculptural, and clearly defined than in Renoir’s earlier work.

So what type of painting is Dance in the Country? It’s a hybrid, a synthesis of Impressionist color and naturalism with classical composition and figuration. It represents a mature Renoir, confident in his vision, blending freedom with control.

The Dance Triptych: A Trio of Celebration

Dance in the Country is one of a trio of paintings Renoir created around the same time, all centered around the theme of dance. The other two are:

Dance in the City (La Danse à la ville)

Dance at Bougival (La Danse à Bougival)

Each painting features a man and a woman dancing, but the settings and moods are distinct:

Dance in the City is elegant and refined, set in an opulent ballroom. The woman wears a pristine white gown, her demeanor formal and reserved. The painting reflects the sophistication and restraint of urban high society.

Dance at Bougival is more dynamic and flirtatious, set in a popular riverside suburb of Paris. The couple is more engaged, more lively, and the brushwork more expressive.

Dance in the Country is the most relaxed and affectionate of the three. It exudes warmth and pastoral charm, a dance not for spectacle but for sheer joy.

Together, these three works form a kind of narrative arc, urban formality, suburban pleasure, and rural serenity. They also reflect Renoir’s exploration of different styles and settings, his ability to convey mood through subtle shifts in posture, expression, and brushstroke.

Where Is Dance in the Country Located Today?

Today, art lovers can experience Dance in the Country in person at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, France. The Musée d’Orsay is one of the world’s premier museums of 19th-century art, housing a stunning collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist masterpieces.

Located on the left bank of the Seine, inside a former Beaux-Arts railway station, the museum is a fitting home for Renoir’s luminous work. Visitors can stand before Dance in the Country, just inches from the canvas, and feel the joy radiating from every brushstroke.

To see the painting in person is to be transported, not just to the French countryside, but into the soul of an era and an artist who believed in the beauty of life’s simplest pleasures.

A Lasting Legacy: Why Dance in the Country Still Matters

More than 140 years after it was painted, Dance in the Country continues to resonate. But why? What is it about this image that speaks to us across time and culture?

Perhaps it’s because, at its heart, this painting is about something we all crave: connection.

In an age of endless distraction, Dance in the Country reminds us of the magic of being truly present with another person. Of moving in harmony, of sharing a laugh, a look, a step. There’s nothing artificial or performative here. Just two people, caught in a moment of shared happiness.

In a world often preoccupied with progress, power, and prestige, Renoir offers us something gentler and more enduring: the beauty of simple joy.

And in Renoir’s world, dance is not just art, it’s life itself, expressed through motion and color, light and love.

The Eternal Waltz of Art and Emotion

Dance in the Country is more than a painting. It’s a love letter to life, written in brushstrokes and sunlight.

Through the soft folds of a dress, the curl of a smile, the dapple of light on a hat brim, Renoir invites us to join the dance. Not as spectators, but as participants. To let go of our burdens, even for a moment, and remember the rhythm that connects us all.

So the next time you see Dance in the Country, whether in person at the Musée d’Orsay or in a book, online, or in your imagination, let yourself step into that gentle country breeze. Let yourself sway with the music you cannot hear but somehow still feel. Let yourself remember what it means to be moved.

Because Renoir didn’t just paint a dance.

He painted joy itself.